Moving closer to the 20th century, philosophers began to question the tenets on which the Enlightenment rested, namely its optimism regarding human rationality and progress. What certainty did man have in values? in the existence of objective truths?

One shy and physically weak Prussian rejected the substance of values and truths with a vehement pen and a joyful irony. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) graduated with a degree in philology (the study of language), but exposure to the work of Schopenhauer in the late 19th century inspired him to explore philosophy. His poor health allowed him much time for contemplation and writing, though eventually his failing eyesight forced him to enlist the help of a student to decipher and transcribe Nietzsche’s chicken scratch.

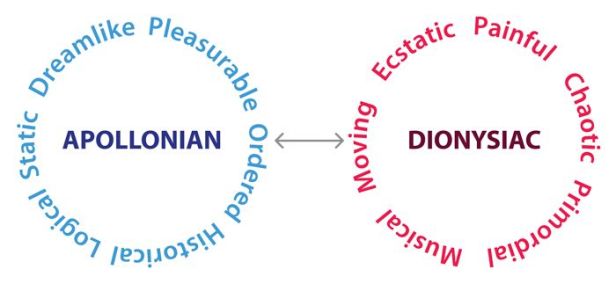

Nietzsche addressed many topics during his three decades of philosophical wandering, among them morality, religion, and language. Among his early books is The Birth of Tragedy (1872), in which he rallied for the resurrection of art, which in a later aphorism he called “the great stimulus to life.” He rejected Socratic rationalism and called for the rebirth of the Apollonian and Dionysian, concepts named after the Greek gods of truth and wine. Their interaction in ancient Greece brought meaning to life, for it produced a frenzy, and in this frenzy alone might man feel powerful enough to transform society.

Nietzsche responded to the question of truth in his essay On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense (written 1873, published 1896). Beginning with an evaluation of human haughtiness, believing themselves to be the focal point of the universe, Nietzsche judged that man survived only by his intellect, lacking the tooth and claw of other creatures. He considered man a being that survives only be simulation – deception, basically – and even in truth deludes himself.

In this essay, Nietzsche peeled back the layers of truth and concluded that the claim of truthfulness is “obligation to lie according to a fixed convention” (On Truth and Lie) Man invented truth to ensure right social interaction, but the truth has no grounding of its own, for man expresses truth in words, which are mere metaphors. They represent concepts; they do not embody the things in themselves.

For an example, Nietzsche explained that the definition and application of honesty comes from “individualized…unequal actions, which we equate by omitting the unequal”, not from the quality itself (On Truth and Lie). This idea falls in line with what Paul Ricœur would call the “hermeneutics of suspicion” – an uncertainty about words meaning what they claim to mean.

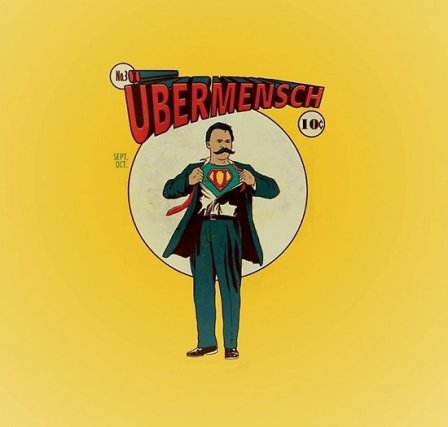

From the 1880s on Nietzsche produced his most well-known works, including Thus Spoke Zarathrusta (1883), an allegory featuring the prophet Zarathrusta [Zoroaster] who preaches on the coming of the Übermensch, translated to English as the Super-man or the Over-man. This character would herald a new standard of morality, what Nietzsche calls master morality in Beyond Good and Evil (1886), a sequel of sorts for Thus Spoke Zarathrusta.

The exaltation of the noble and the powerful and condemnation of the despicable and decaying characterizes the master morality. The Over-man of perfect master morality knows himself to be the creator and judge of law and order. The antithesis of the Over-man is the Last Man and his slave morality, which opposes the will to power that Nietzsche saw as driving all great human achievement. The Last Man regards power as evil; that which is safe and serves the weaker man, as good. He champions the “soft” qualities of sympathy, humility, and others. To the slave morality Nietzsche associated religion, particularly Christianity.

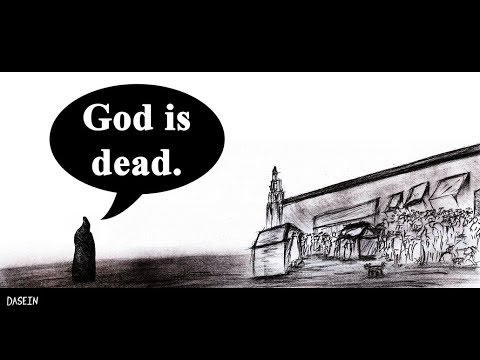

Nietzsche encouraged readers to shake free of the impediments of religion. In The Gay Science (1882) he describes a madman running through a village and seeking God. “Whither is God?” he cried, then, “I shall tell you. We have killed him – you and I. All of us are his murderers…How shall we, the murderers of all murderers, comfort ourselves?” (Aphorism 125). To this frenzy Nietzsche responds with optimism later in the book: like a lake dammed, man will “ever rise higher and higher…when he no longer flows out into a God” (Aphorism 285).

The rejection of objective values and truth – or truth at all, for that matter – of God Nietzsche, optimistic though he may have been, recognized as a movement that would slam Europe into the chaotic abyss of nihilism. In a collection of aphorisms published posthumously, Nietzsche predicted,

“What I relate is the history of the next two centuries. I describe what is coming, what can no longer come differently: the advent of nihilism. . . . For some time now our whole European culture has been moving as toward a catastrophe, with a tortured tension that is growing from decade to decade: restlessly, violently, headlong, like a river that wants to reach the end” (The Will to Power, aphorism 2).

The prophecy came true when the world erupted in two wars and the ideologies formed through the 19th and 20th centuries crumbled. Confidence in human reason and science that developed during the Enlightenment, in question already by existentialists like Nietzsche, fell in the face of World War II’s traumas.

In your opening sentence, it should be “question the tenets on which the Enlightenment rested,” not “question the tenants on which the Enlightenment rested,” unless you do want to posit the Enlightenment as some overbearing, conniving landlord.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good catch! Thanks for letting me know. I’ll be sure to edit that section.

LikeLike